Guidelines for Sleep Environments in Spaceflight Missions

Objective

We had three main objectives:

• to conduct a review of the evidence surrounding the optimal characteristics for the sleep environment in the categories of noise, temperature, lighting, and air quality in order to provide specific recommendations for each of these components,

• review relevant evidence from prior human spaceflight missions and spaceflight analog environments, and

• to interview relevant subject-matter experts who have experience sleeping and living in extreme environments.

• review relevant evidence from prior human spaceflight missions and spaceflight analog environments, and

• to interview relevant subject-matter experts who have experience sleeping and living in extreme environments.

Background

Current evidence demonstrates that astronauts experience sleep loss and circadian desynchronization during spaceflight. Ground-based evidence demonstrates that these conditions lead to reduced performance, increased risk of injuries and accidents, and short and long-term health consequences. Many of the factors contributing to these conditions relate to the habitability of the sleep environment. Noise, inadequate temperature and airflow, and inappropriate lighting and light pollution have each been associated with sleep loss and circadian misalignment during spaceflight operations and on Earth. As NASA prepares to send astronauts on long-duration, deep space missions, it is critical that the habitability of the sleep environment provide adequate mitigations for potential sleep disruptors.

My role and responsibilities

My primary responsibilities included conducting literature reviews, report writing, creating and organizing a digital library, creating interview questions, note-taking during interviews, and presenting results to wider scientific audiences

Methods and Approach

Literature Review:

We conducted a comprehensive literature review summarizing optimal sleep hygiene parameters for lighting, temperature, airflow, humidity, comfort, intermittent and erratic sounds, and privacy and security in the sleep environment. We reviewed the design and use of sleep environments in a wide range of cohorts including among aquanauts, expeditioners, pilots, military personnel, and ship operators.

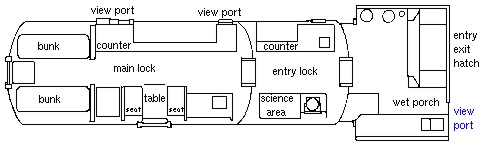

Figure 1. Aquarius' habitat layout. Aquarius sits at a depth of 60 feet and is used as an analog for long-duration spaceflight.

Figure 2. Ocean view of Aquarius. Underwater environments, like spaceflight, offer a constant source of danger from treacherous surroundings, which cannot be easily escaped. Aquanauts, like astronauts, have the looming threat of decompression sickness, or "the bends," when venturing outside of their protected environment. Additionally, the key to survival rests upon technology, highly specialized skill sets, as well as communication and assistance from ground level support teams.

Spaceflight Data Review:

We also reviewed the specifications and sleep quality data arising from every NASA spaceflight mission, beginning with Gemini.

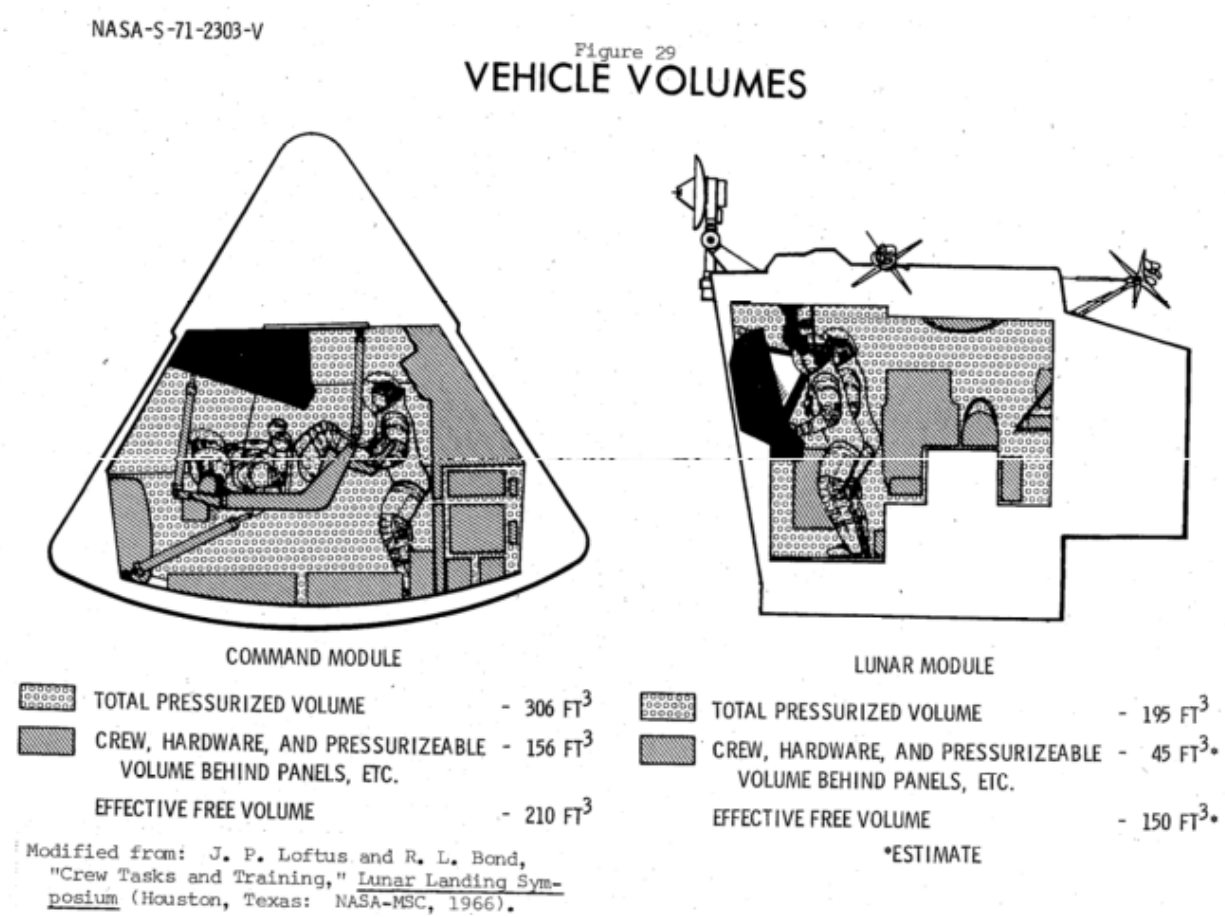

Figure 3. Apollo vehicle volumes.

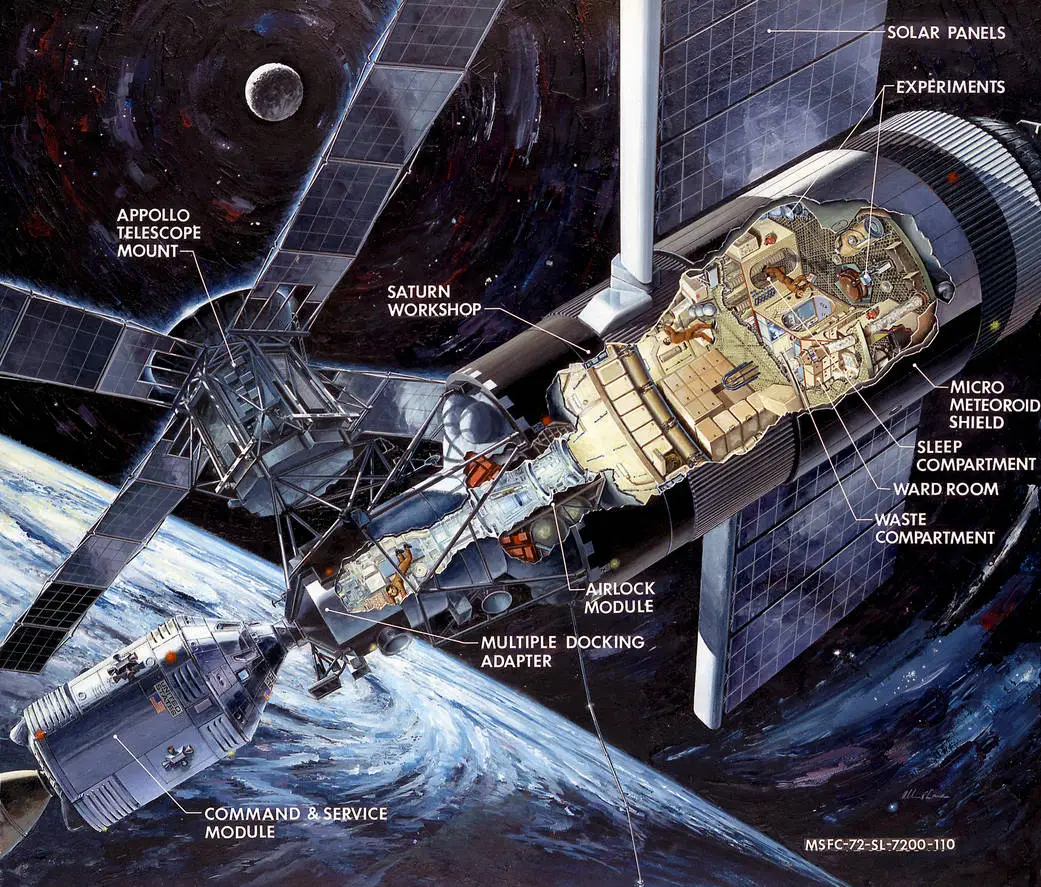

Figure 4. Skylab artist concept.

Figure 5. Crew Quarters on the International Space Station.

Interviews:

Finally, we conducted structured interviews with individuals experienced in sleeping in non-traditional spaces, such as oil rig workers, Navy personnel, astronauts, and expeditioners. In addition, we interviewed engineers responsible for designing the sleeping quarters currently deployed on the International Space Station.

Findings

We found that the optimal sleep environment is cool, dark, quiet, and is perceived as safe and private. There are wide individual differences in the preferred sleep environment; therefore modifiable sleeping compartments are necessary to ensure all crewmembers are able to select personalized configurations for optimal sleep. A sub-optimal sleep environment is tolerable for only a limited time, therefore individual sleeping quarters should be designed for long-duration missions. In a confined space, the sleep environment serves a dual purpose as a place to sleep, but also as a place for storing personal items and as a place for privacy during non-sleep times. This need for privacy during sleep and wake appears to be critically important to the psychological well-being of crewmembers on long-duration missions.

A summary of specific recommendations is presented in the table below.

| Topic | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Sleep Station Location |

• Sleep stations should be located away from common areas such as the galley.

• Sleep stations in near proximity to lavatories, but should be separated by a distance sufficient to minimize noise from the waste management systems. • If watch schedules are used, then crew sleep stations should be situated away from the command center in order to minimize noise from communication with Mission Control and equipment. |

| Privacy |

• Crewmembers should be provided with private crew quarters for optimal sleep health during deep space missions and for spending time away from other crewmembers.

• Space for storing personal items should be accommodated in sleep stations. • Customization of the sleep environment should be allowed. • Hot bunking is associated with poor sleep quality, negative mood, and poor health and hygiene and should be avoided. |

| Habitable Volume |

• The habitable volume of the sleep chambers for deep spaceflight should be a minimum of 2.1 m3. Larger chambers may be required for taller crewmembers.

• Based on previous missions, the habitable volume for a planetary excursion should have minimum individual crew quarters of 2.8 m2 in order to account for the reduction in usable space and to accommodate a bed, personal workspace and personal storage space. However, crew quarters of 5.4 m3 are recommended as there will be an increase need for privacy in response to the unprecedented nature of future planetary missions. • The minimum habitable volume for extended duration missions (i.e. longer than one year) was determined to be 25 m3 (883 ft3) per person. |

| Sleep Environment Lighting |

• Complete darkness is optimal for sleep. Sleeping quarters should be able to be darkened completely.

• Light pollution from other areas should be eliminated. • Indicator lights should be used only when necessary and should be dim and red. • Eye masks should be available to crewmembers. • Mimicking sunrise/sunset with some proportion of the common area lights may be desirable. |

| Noise |

• All forms of noise should be below 35 dB in sleeping quarters.

• Familiar noise, such as human voices, is disruptive to sleep at lower decibels, so noise mitigations to protect against noise pollution from common areas is important. • Intermittent noise is more disruptive to sleep than continuous noise and should not vary by more than 5 dB from background noise. • Continuous white noise of <25 dB may be useful to protect sleep by buffering other noises, but its use should be controlled by the crewmember. • Earplugs and noise canceling headphones should be made available to crewmembers. • The depth of sleep and individual differences predict arousal from auditory alarms. Multi-sensory alarms may be desirable. |

| Temperature |

• Ambient temperature should be maintained between 18.3-22˚C (65-72˚F) during sleep (assuming adequate bedding is available, cooler is better. When no insulation is available, hotter temperatures are required).

• Crewmembers should have control of ambient temperature within the normal range in order to account for individual preferences. • Humidity should be between 40-60% relative to ambient temperature. • Sufficient bedding should be provided to allow crewmembers to achieve a microclimate 25-35˚C (77-95˚F). • Bedding should be modifiable, so that crewmembers can add or remove insulation based on individual preferences. • Providing socks or local heating sources to allow for the warming of proximal and distal skin temperature during sleep may facilitate sleep onset. |

| Air Quality |

• The optimal ambient gas mixture for sleep is equivalent to the air experienced at sea level on Earth (78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 1% other gases).

• The optimal air pressure during sleep is equivalent to the pressure on the Earth at sea level. • In depressurized environments, such as at elevation on Earth, supplemental oxygen can reduce headaches, periodic breathing and can improve sleep outcomes. • Adequate ventilation should be provided for the reduction of CO2 and for the reduction of intrusive odors. • Air velocity should be between 12-36 meters/minute. • Air filters should be used to remove contamination from particulates and dust, particularly that emanating from a planetary excursion. |

| Comfort |

Microgravity environment

• The bedding provided during spaceflight should:

Planetary excursion environment

• allow for crewmembers to strap themselves to the inside of a sleep station if desired.

• be easily cleaned.

• The bedding provided for a planetary excursion should:

• allow for horizontal positioning on a flat surface.

• be sized to accommodate movement during sleep and changes in body position. • provide natural fiber bedding for breathability. • provide a medium-firm mattress, blankets and • pillows selected by the crewmember. |

| Turbulence |

• Vehicle movement should be minimized in order to facilitate sleep. When vehicle movement occurs, the sleep opportunity should be lengthened to allow for adequate sleep

|

| Safety |

• Uncertainty about safety can induce anxiety, leading to sleep disruption. Clear and accurate information about safety hazards should be provided to crewmembers in order to alleviate stress due to false alarms regarding safety.

|

| Backup Systems |

• Given the importance of sleep quality, there should be an emergency deployable sleep station and thermal blankets in the event that a sleep station is damaged.

|

Significance

The research undertaken has numerous applications and implications. This project is a comprehensive exploration into creating the ideal sleep environment in challenging conditions, especially space. Its findings could have significant implications for the health and effectiveness of astronauts on future long-duration space missions. Additionally, our sleep guidelines provide recommendations for the health of individuals but also for architectural designs of living spaces. This has broader implications, suggesting that homes, hotels, and other residential structures can be designed with these findings in mind to promote better sleep quality and general health.

Collaborators

Erin Flynn-Evans (principal investigator)

Kevin Gregory (researcher)

Lucia Arsintescu (researcher)

Associated Publications

Journal Article:

Caddick, Z.A., Gregory, K., Arsintescu, L., Flynn-Evans, E.E. (2018, March). A Review of the Environmental Parameters Necessary for an Optimal Sleep Environment. Building and Environment. 132, pp. 11-20. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.01.020

Conference Paper:

Caddick, Z.A., Gregory, K, and Flynn-Evans, E.E. (2016, July). Sleep Environment Recommendations for Future Spaceflight Vehicles. Advances in Human Aspects of Transportation. 484, pp. 923-933. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41682-3_76

NASA Technical Report:

Flynn-Evans, E.E., Caddick, Z.A., and Gregory, K. (2016, December). Sleep Environment Recommendations for Future Spaceflight Vehicles. NASA/TM-2016-219282

Caddick, Z.A., Gregory, K., Arsintescu, L., Flynn-Evans, E.E. (2018, March). A Review of the Environmental Parameters Necessary for an Optimal Sleep Environment. Building and Environment. 132, pp. 11-20. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2018.01.020

Conference Paper:

Caddick, Z.A., Gregory, K, and Flynn-Evans, E.E. (2016, July). Sleep Environment Recommendations for Future Spaceflight Vehicles. Advances in Human Aspects of Transportation. 484, pp. 923-933. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-41682-3_76

NASA Technical Report:

Flynn-Evans, E.E., Caddick, Z.A., and Gregory, K. (2016, December). Sleep Environment Recommendations for Future Spaceflight Vehicles. NASA/TM-2016-219282

Tools and Software Used

Mendeley, EndNote, used various scientific search engines (e.g., Google Scholar, PubMed) and databases including NASA's libraries.

Resources

1 The journal article can be downloaded here.

2 The conference paper can be downloaded here.

3 The NASA Technical Report can be downloaded here.