Designing a Microworld to Study Human Learning

Objective

The goal of this project was to examine how people's prior beliefs influence decision-making. Participants will be in an environment where they learn over time and where some relationships may be ambiguous or challenging to uncover.

Background

Humans are often faced with the task of evaluating the efficacy of an action or policy in dynamic settings, which can be very challenging. Assessing the true impact of the policy is likely to be very difficult because other factors in the economy also change over time, and because one’s expectations about how fast the policy will work and the short versus long-term impacts of the policy could lead different people to focus on different evidence. Furthermore, in many situations, an individual might have strong preferences or engage in wishful thinking or “motivated reasoning”, which could bias their interpretations of the evidence.

My role and responsibilities

I was a graduate student researcher on this project, which was my master's thesis at the University of Pittsburgh. With a few exceptions, I wrote all of the code involved in this project. This included website back-end & front-end development, in addition to the data munging and analyses. I also wrote initial drafts of the report writing for this project and collaborated with my advisor on edits.

Methods and Approach

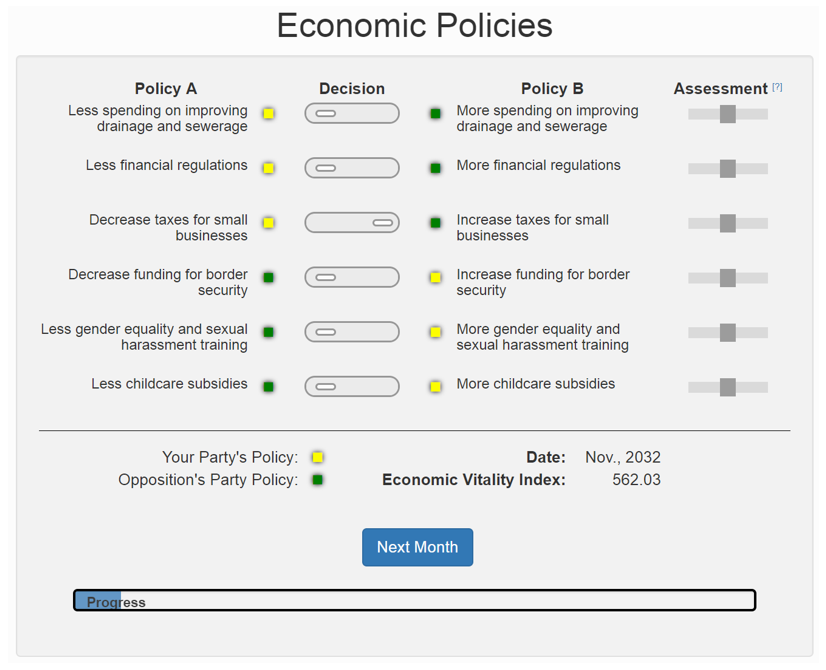

Participants are tasked with leading a fictional country. Their main objective is to optimize the Economic Vitality Index (EVI), a metric similar to GDP.

Procedure:

1. Beliefs Survey: Participants answered questions regarding their views on economic policies. This helped select policies they felt strongly about.

2. Economic Policy Task: Over 140 months (each trial representing a month), participants decided between two versions of six different policies to maximize the EVI.

3. Post-task Survey: Participants shared insights about their decisions and took a general questionnaire.

2. Economic Policy Task: Over 140 months (each trial representing a month), participants decided between two versions of six different policies to maximize the EVI.

3. Post-task Survey: Participants shared insights about their decisions and took a general questionnaire.

Task Details:

For each of the six policies, participants chose between Policy A and B. Outcomes of policies varied:

• Two policies showed rapid effects.

• Two policies had ambiguous short-term vs. long-term impacts.

• Two policies (termed “non-causal”) had no significant difference between their versions.

• Two policies had ambiguous short-term vs. long-term impacts.

• Two policies (termed “non-causal”) had no significant difference between their versions.

Key Investigative Goals:

1. Understand the process of testing and learning.

2. Determine if political preferences affected choices during and after the learning phase.

3. Analyze the effect of policy ambiguity on the above aspects.

4. Assess influence of strong vs. neutral preferences.

5. Explore if prior knowledge on potential causal impacts influenced decisions.

2. Determine if political preferences affected choices during and after the learning phase.

3. Analyze the effect of policy ambiguity on the above aspects.

4. Assess influence of strong vs. neutral preferences.

5. Explore if prior knowledge on potential causal impacts influenced decisions.

Figure 1. Screenshot of the economic learning task. On each trial, participants decide between Policy A and B for each of the six policies. In order to maximize the Economic Vitality Index on each trial, participants can update their beliefs about which policy is better using the assessment slider. Participants chose the color to represent their party, and this color indicates the participant’s preferred policy stance as previously self-reported. The task lasts for 140 months where each trial is a month.

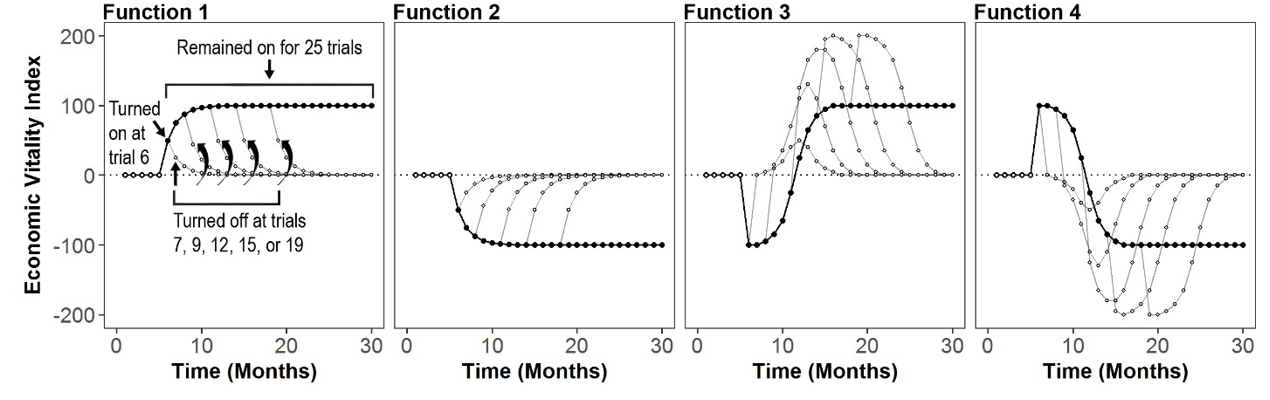

A mathematical function was randomized to each of the 6 policies.

Figure 2. Illustrations of the payoff functions. Note: The first five trials in every graph represent an input of “off” (white dots). The solid black line shows the function if it is turn on at Trial 6 and left on until Trial 30. The gray lines show the pattern economic output if the function is turned “off” on Trial 7, 9, 12, 15, or 19, instead of being left on. Functions 1 and 2 are the “low ambiguity” (short-term and long-term effects match). Functions 3 and 4 are the “high ambiguity” (short-term and long-term effects are mismatched). Functions 5 and 6 (omitted) did not have any effect.

Note: Some technical details have been intentionally omitted to simplify the overview. The actual research paper contains a comprehensive breakdown for those wanting a deeper dive.

Findings

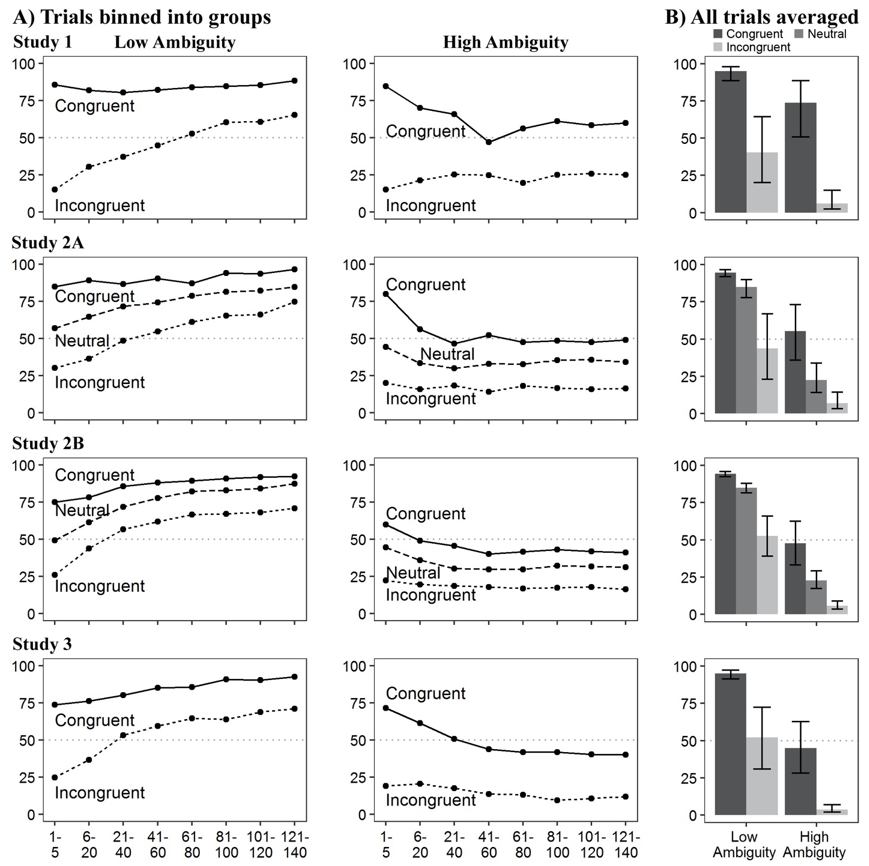

In three studies, we found evidence of motivated reasoning despite financial incentives for accuracy. For example, participants who believed that border security funding should be increased were more likely to conclude that increasing border security funding actually caused a better economy in the task. In Study 2, we hypothesized that having neutral preferences (e.g., preferring neither increased nor decreased spending on border security) would lead to more accurate assessments overall, compared to having a strong initial preference; however, we did not find evidence for such an effect. In Study 3, we tested whether providing participants with possible functional forms of the policies (e.g., the policy takes some time to work or initially has a negative influence but eventually a positive influence) would lead to a smaller influence of motivated reasoning but found little evidence for this effect.

In three studies, we found that participants were more likely to select the optimal policy if it agreed with participants' prior belief and if it was less-ambiguous.

Figure 3. (a) Represents learning curves. Over time participants tend to choose the optimal policy for the low ambiguity functions but are less successful for the high ambiguity functions. Additionally, participants were more likely to choose the optimal policy when it was preference-congruent (i.e., their preferred policy was optimal) than preference-incongruent (i.e., their preferred policy was not optimal); (b) collapses the data in (a) across the 140 trials. Note: Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Chance is 50%.

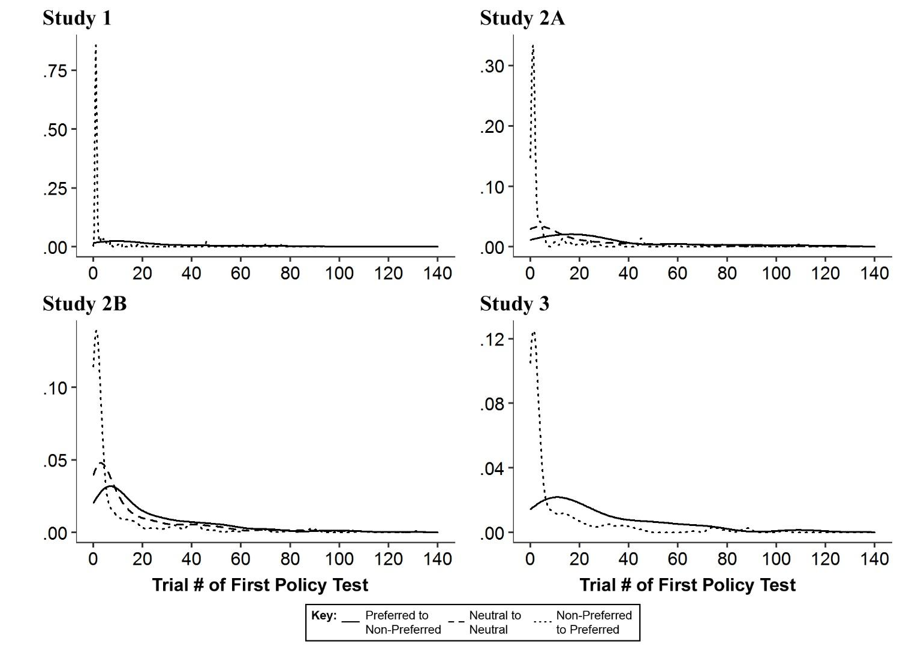

We also examined how strategy influenced participants decision-making. For instance, we found that participants would typically set all policies not initially set to their preferred policy to their preferred policy at the start of the experiment, which hindered their ability to learn each policy's effect. This striking pattern is evident in the figure below.

Figure 4. Density plots for the number of trials until testing by preference. Note: The Y-axis is the density probability estimation for first testing a policy. The X-axis is the trial range (1–140) for the learning task. All four studies show that participants quickly switched non-preferred policies to preferred and switched preferred policies to non-preferred later. Neutral policies tended to be switched after non-preferred policies and before preferred

Not only did participant set non-preferred policies to preferred policies immediately, but they did this in mass. This is a problematic because it makes it impossible to understand the individual effects of a single policy.

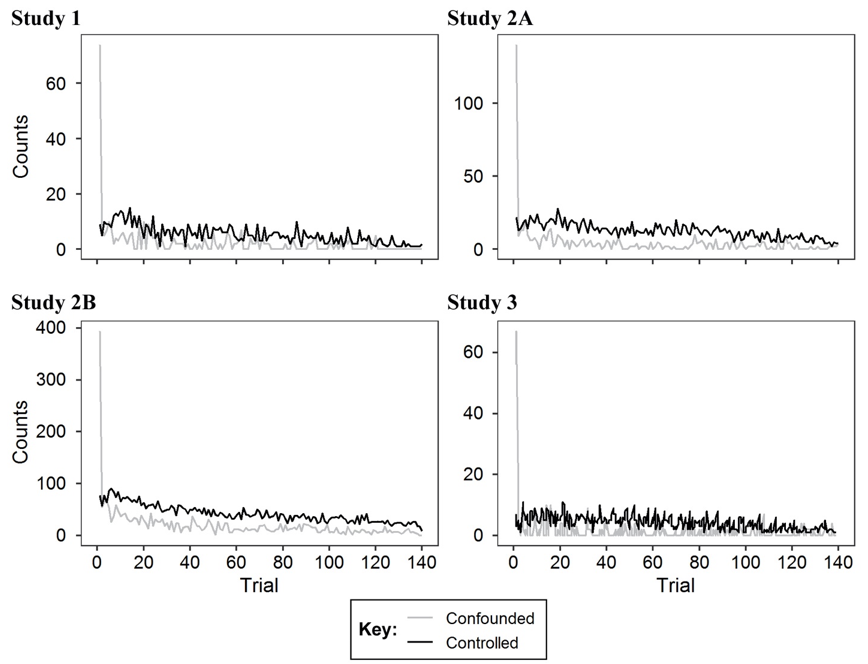

Figure 5. During Trial 1 participants mainly made confounded changes (changes to two or more policies), and for the rest of the trials, participants mainly made controlled changes (changes to a single policy). Over the course of the study, participants made fewer policy changes as they settled on the policies they thought were best.

Real-world Implications: The study's findings have crucial implications for real-world policy-making and evaluation. For instance, the tendency for individuals (or policymakers) to quickly align policies with their personal preferences can hinder objective evaluation and the potential discovery of optimal policies.

Challenges with Ambiguity: In the world of decision-making, many policies might have ambiguous outcomes. The difficulty participants faced in discerning such policies speaks to the challenges policymakers face, especially when short-term gains might be at odds with long-term outcomes.

Potential for Improved Learning Mechanisms: The limited success of prior knowledge in enhancing participants' understanding suggests there's room for research into more effective teaching or exposure methodologies that can enhance decision-making in ambiguous scenarios.

If you would like to learn about more of the results and finding, check out the full publication.

Significance

This research advances the field of causal learning by studying the role of prior preferences, and in doing so, integrates the fields of causal learning and motivated reasoning using a novel explore-exploit task.

Collaborators

Benjamin Rottman (academic advisor/principal investigator)

Publication

Caddick, Z.A., Rottman, B.M. (2021). Motivated reasoning in an explore-exploit task. Cognitive Science, 45(8), e13018. doi:10.1111/cogs.13018

Tools and Software Used

Qualtrics, MTurk, R (tidyverse, & ~15 other packages), Python (google app engine, numpy, random, django, & more), JavaScript (jquery, bootstrap), Adobe Photoshop.

Resources

1 The journal article can be downloaded here.

2 I have posted the datasets and analysis scripts for this project on github.

3 The websites I programmed for the experiments are still online and can be experienced. (Although the Qualtrics survey portion that occurs after the behavioral task is no longer available.) Here are the websites for each study: Study 1, Study 2, Study 3.

The first page asking for a "MTurk ID" can be bypassed by entering in a username it has not seen before (feel free to button mash). Since I am no longer collecting real data anymore, it doesn't matter!

If you would like to peruse the study without having to answer all the questions, I wrote console commands to move more quickly through the tasks.

You can skip from the policy question screen (the one with 66 questions), but entering "Exp_Skip()" into the console. This function will autofill all answers so you can proceed to the next screen.

In the main behavioral task (the one where you choose policies to maximize the economic output), you can enter "delay=0" into the console to allow for the "Next Month" button to be clicked more rapidly.